Moments after the news of Charlie Hebdo hit my screen, I felt the need to do something. #JeSuisCharlie was already trending and writers and artists and free-thinkers I admired and respected were posting photos of broken pencils … which moved me deeply and made me want to rise up with all the other pencils and sharpen.

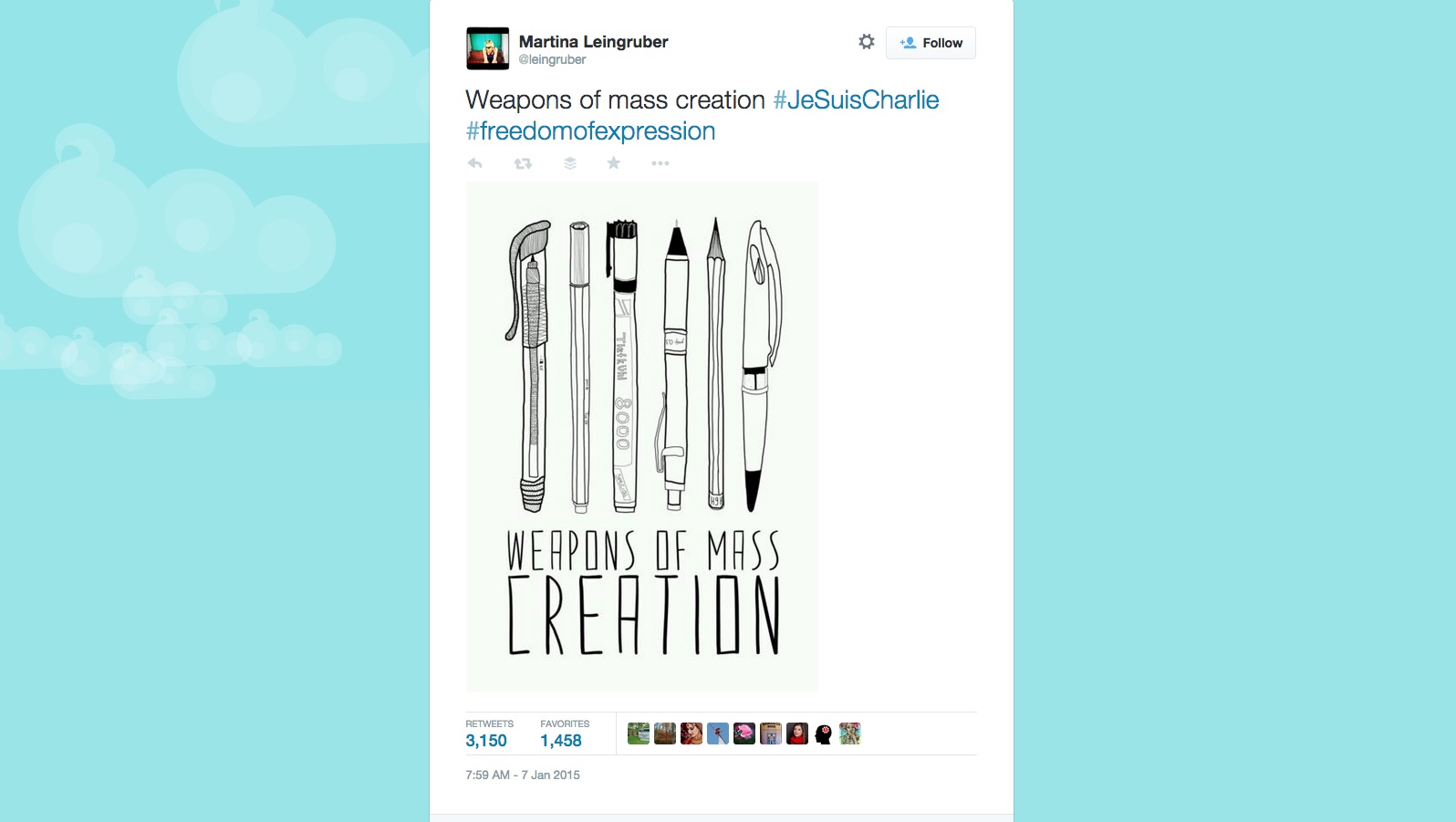

I retweeted a picture of pens in a row. "Weapons of Mass Creation," it read, and I sat down to think about what that truly meant.

Weapons of mass creation #JeSuisCharlie #freedomofexpression — Martina Leingruber (@leingruber) January 7, 2015

What do we create with our words? With our pictures? With our photographs? What do we build with our voices? Who do we rally behind? Antagonize? Support? Stand with? Listen to? Epitomize? For those of us who spend the bulk of our lives creating, who is our audience? And why?

The more I though of my retweet, the more I realized how much more thinking I had to do before I hashtagged anything.

My heart was broken for those viciously massacred. It still is. I mourned for Paris then and I mourn for Paris now. I also mourn for Nigeria and our all-too-violent world. I abhor violence of any kind and believe with my whole heart in peaceful protest, in joining hands and marching for peace, for everywhere and everyone. I believe in creative freedom and a world without censors. I believe that creative expression is a basic human need, that storytelling is our greatest asset as a species.

I must show my solidarity to a magazine of free-thinkers because I am a free-thinker, too. Because without free speech I am nothing. We, as humans, are nothing.

And yet, without free thought, we are even less.

Earlier this week, Saladin Ahmed wrote the following:

Why don't I feel like one of the good guys? Why do I, instead feel like part of the problem? From where I stand, I see one way. And from where others stand, they see something else. And when we all march together in a line in the same direction, what does that mean? What does it mean when we ignore atrocities elsewhere without calling ourselves Nigeria, for example (#naijanimi), and when we ignore that we, the so-called "good guys," are seen as terrorists in many parts of the world?

Why don't I feel like one of the good guys? Why do I, instead feel like part of the problem? From where I stand, I see one way. And from where others stand, they see something else.

But we're the good guys!

We don't have time to really think about it. We don't want to have the time. Nuance complicates everything. Nuance makes superheroes less heroic and humanizes villains. Nuance forces us to look in our cultural mirrors and recognize that nobody is innocent.

Nobody.

We don't have time to ask ourselves these questions and we refuse to look in the mirror. Instead we follow the mob. We take the signs we are handed and we go into battle. That is how wars have always been fought and won.

But at what cost? And who is the general? Who are we fighting? And why do they want to fight us? The answers will never be clear to us because we are over here. We are in our homes, in our cities, in our skin, in our own experiences. Scott Long writes on his blog, A Paper Bird:

But …

Wait.

I don't care that Voltaire didn't actually say this, it's still a noble sentiment. But it's also woefully false. Are we really willing to fight to the death to protect a person's right to use racial slurs and threaten rape in comments sections? I'm not. I do not want to fight to the death so that people, friends, even strangers, may be shamed and/or threatened. Do you?

Words have the power to change minds and turn hearts and kill spirits.

Growing up, the kids on the playground used to say, "It's a free country!" in order to defend their words, their actions, regardless of how cruel they were.

"I can say whatever I want to say to you, OK? _It's a free countr_y."

And they were right. But they were also completely wrong.

Nothing is free. Everything comes with and at a cost. If not to me or you, to someone.

The cold never bothered me anyway.

Censorship is not for governments or world leaders. It is not something we should be "bullied into doing." It is, however, something we must be mindful of when it comes to our OWN words and phrases. Knowing how and why and when to self-censor is crucial. It isn't "cowardice" to censor what we know will sting another—it's empathy.

In the words of Rabbi Michael Lerner (who wrote a must-read, in my opinion):

Words have the power to change minds and turn hearts and kill spirits. Power is in words and images and we all have a responsibility that extends beyond our voices and into the ears and eyes of our audiences.

Shouldn't we take some responsibility for the way we marginalize others? The way we belittle and humiliate? If you put a tiger in a cage and taunt it, what happens? (Hell, if you put anything in a cage and taunt it, over time, what happens?) If you bully an outcast for long enough, what happens? If you draw pictures hyperbolizing ethnicity and paste them to the mirrors and doors, windows and ceilings of your subjects, what then?

"I'm marching but I'm conscious of the confusion and hypocrisy of the situation." — Dalia Ezzat (@DaliaEzzat_) January 11, 2015

There is a noticeable difference in tone between those who have reacted first and those who waited a few days before publishing, for example this piece by Roxane Gay:

In the words of Ta-Nehisi Coates via his piece "I Might Be Charlie":

"I have so much to tell you, but it's raw and unseasoned. I need some time to marinate and then cook."

Yes.

Me too.