When Jessica Patay gave birth to her second son, Ryan, she and her husband knew something wasn't quite right. He didn't suck to eat, he didn't cry. In fact, he barely moved. He was very sleepy and didn't rouse to eat. Doctors diagnosed him with "failure to thrive," and, for his first four weeks of life, he stayed in the hospital on a feeding tube.

At 5 weeks, their pediatrician called with results of a DNA test, part of a screening that Jessica's husband, Chris, pushed for after Googling his son's symptoms. The test, as well as the symptoms, led doctor's to confirm that Ryan was born with Prader-Willi syndrome, a spectrum disorder.

"We were heartbroken, yet relieved to have a framework to understand his strange symptoms and needs," Jessica told me. "It felt like we landed on The Crazy Planet, and all we wanted to do was get back home to normal."

RELATED: My Son Has a Syndrome. I'm Over It.

With the diagnosis, and support from parents who had been in their shoes, they adjusted and embraced this New Normal. "Chris has always been a hands-on dad and for that I am grateful every day," she said.

It took Ryan almost a year to gain the strength and ability to suck on his own. Just before his first birthday, his feeding tube was removed.

Early on, Chris had connected with the Prader-Willi California Foundation, who put them in touch with a parent mentor. Lisa Graziano provided comfort and advice on the next steps for Ryan's care.

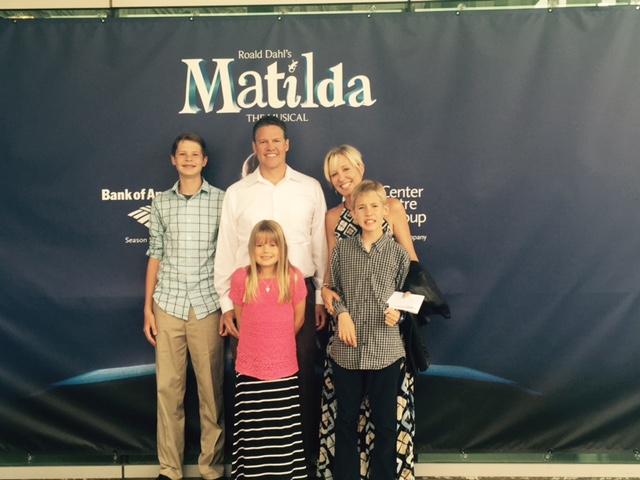

Today, the Patays have three children: Luke ,15, Ryan, now 12 and Kate, 10.

Until two years ago, Jessica worked in fashion sales. She has since stepped down to be at home due to rising challenges with Ryan.

Jessica says their family has benefitted from the PWCF support groups and the friends they have made who are struggling along besides them. The PWCF provides education, an annual conference, resources, advocacy, support groups and much more.

Ryan has received occupational therapy, feeding skills when he was little, fine motor skills now, and physical and speech therapy. He has a 1:1 aid with him at school all day and will always have one while in the school years. The most concentrated services came during the three year following his diagnosis as a newborn.

Prader-Willi syndrome isn't a very well-known spectrum disorder, so Jessica and her family had to dig deep to understand all there is to know. Here are five facts that she thinks everyone should know about it.

1. PWS is a multi-faceted spectrum disorder

The most "famous" symptom of PWS is hyperphagia, the excessive seeking of food, the insatiable appetite. What makes the news of course is some disabled, obese kid running down the street after the ice cream truck in a mad tantrum demanding treats. However, PWS encompasses all these systems of the body:

- Neurological (cognitive deficits)

- Endocrine system impairments (requiring daily injections of growth hormone; extremely low metabolism)

- Gastrointestinal (slow emptying stomach, swallow dysfunctions)

- Musculoskeletal (scoliosis is common)

- Central nervous system impairments causing problems with sleep cycles, temperature regulations, pain regulation and breathing (sleep apnea)

- Mobility (hypotonia leads to a host of issues and delays)

- Psychiatric (moderate to severe anxiety, OCD, psychotic breaks with reality)

- Educational (requiring Individualized Educational Plan supports in school)

- Behavioral issues similar to autism (rigid, stubborn, perseverative__,__ obsessive, tantrums, aggression)

The hyperphagia and lower metabolism creates a deadly combination that leads to morbid obesity and all of the health problems—diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, high blood pressure, etc.—that come with obesity. But just because someone has PWS does not mean that obesity can't be prevented.

With proper food management and regular exercise, a healthy weight can be maintained. With an early diagnosis and proper management from the start, obesity can be avoided.

"Looking at Ryan and knowing nothing about PWS, aside from the propensity toward early obesity, you'd never know he has PWS because Chris and I have been diligent about providing food security," Jessica said.

The overwhelming, insatiable drive to get food is not the most difficult piece to manage, she says. Although, it is true that most families have their refrigerators and pantries locked 24/7 to protect their children from stealing food and from eating as much food as is available until discovered, which is life-threatening to a person with PWS.

"We do not have anything locked up, and his food drive does not seem to be as strong as others," she said. For now, the Patay's remain on alert. "Our daily stress really comes from Ryan's anxiety. He is upset easily by changes in the day, by what we say, if he doesn't get what he wants and by not easily understanding how the world around him works. As a family, we walk on eggshells at times. We have been medicating him the last two years, but it does not cure or fix the anxiety." Their family has undergone countless hours of behavioral training and instruction, as a means of reducing Ryan's anxiety and family stress.

2. No one has ever heard of PWS

Because it is so complex and multi-faceted, Patay says it is hard to be concise and give a cocktail-party answer to, "What is it?" The quickest answer? "He is developmentally delayed and appears autistic. But yet it's so much more than that," she says.

The Patays, therefore, are responsible for educating everyone in Ryan's path: doctors, teachers, therapists, school aids, babysitters, family, friends and other special needs parents. "Chris and I have been extremely open from the beginning, sharing our story with anyone kind enough to listen" she says.

The chances of a child being born with this random fluke is 1 in 15,000 births. It happens across all races/ethnicities/genders.

3. PWS is lifelong

This is not a childhood disorder that can be cured or grown out of. In fact, issues become more complex and challenging as children grow up. It. Does. Not. Get. Easier.

Can you imagine a grown man-child having a tantrum over food? Children and adults need constant, consistent supervision, structure, diet, exercise and schedules. Even if one adult is considered "high-functioning," he or she will never live alone, be independent, drive a car, get married, have children. Never say never, but the majority will grow up without these milestones. Because of the food obsession piece alone, an adult with PWS can almost never be unsupervised.

"Ryan will always live with us or in a group home for adults with PWS," Jessica says. "There is a growing need for services for disabled adults."

4. Children and adults with PWS want social connections

They are very sweet, and caring, and do seek out social time with peers. Yet because they are egocentric and have difficulty seeing others' point of views or needs, they struggle in friendships. They tend to be rigid, possessive and stubborn. Lying and making up the rules to games are not tolerated easily.

Much like in autism, kids with the syndrome miss social cues and facial expressions. Fine motor or gross motor issues interfere with their ability to play sports or certain activities with typical peers. Children with the syndrome tend to gravitate toward adults, because they have been around so many since birth and because adults tend to be the most patient and willing to listen to them.

"As a mom, and as a person who highly values her deep friendships, this is so very sad to me,"Jessica says. "Ryan seems to be at times unaware of this deficit in his life. As he has gotten older—he's in 6th grade— and sees Luke and Kate have so much social time, he asks for it. It's not an easy request to fill. When he is in a group home some day with other PWS adults/peers, I hope that need will be fulfilled.

RELATED: Leave Chrissy Teigen and Her Night Nurse Plans Alone

5. PWS is rare, not well understood and underfunded

PWCF is the only organization in California, where the Patay's live, that exclusively serves PWS families. PWCF works closely with PWSA (USA), the national organization based in Florida. Both are severely underfunded. More money is need to better research and understand the syndrome. And funds are also needed to support families of children born with PWS, as well as the PWS adults that they become.

Photographs by: Jessica Patay