What straight people don’t understand about being secretly gay is that it’s all about power — and who you give it to. When I was 19 years old and starting to come out to my first few friends, they now had all of the power. Before that, I’d spent my life in a self-imposed cocoon, believing that any of my authentic reactions and impulses were shameful and cause for rejection. Internally, I flailed around in the dark, not sure of why I felt wrong, while the major difference between who I tried to be and literally everything about my internet search history was getting harder to ignore.

Finally, for one stupid reason or another, you accept it: You’re gay! Then, what do you do with the power you gain from recognizing your first major personal truth? You put it in the hands of other people, of course. You, a shaking newborn, sit someone down, and through a quiver in your voice, ask someone for the first time in your life: “Do you like me for me?”

By 23, I was over it.

Being secretly gay and then coming out is a weapon. It disarms strangers who have their guard up. It transforms natives into tourists, so accustomed to spaces of hetero-domination that anything different becomes worthy of curiosity and attraction. And, by 23, I’d learned that I could use it to attack. The target? My mother, from whom I was newly independent. I was searching for ways to throw the power grip she’d held over me all through adolescence back in her face.

Photo courtesy of Ross Baron

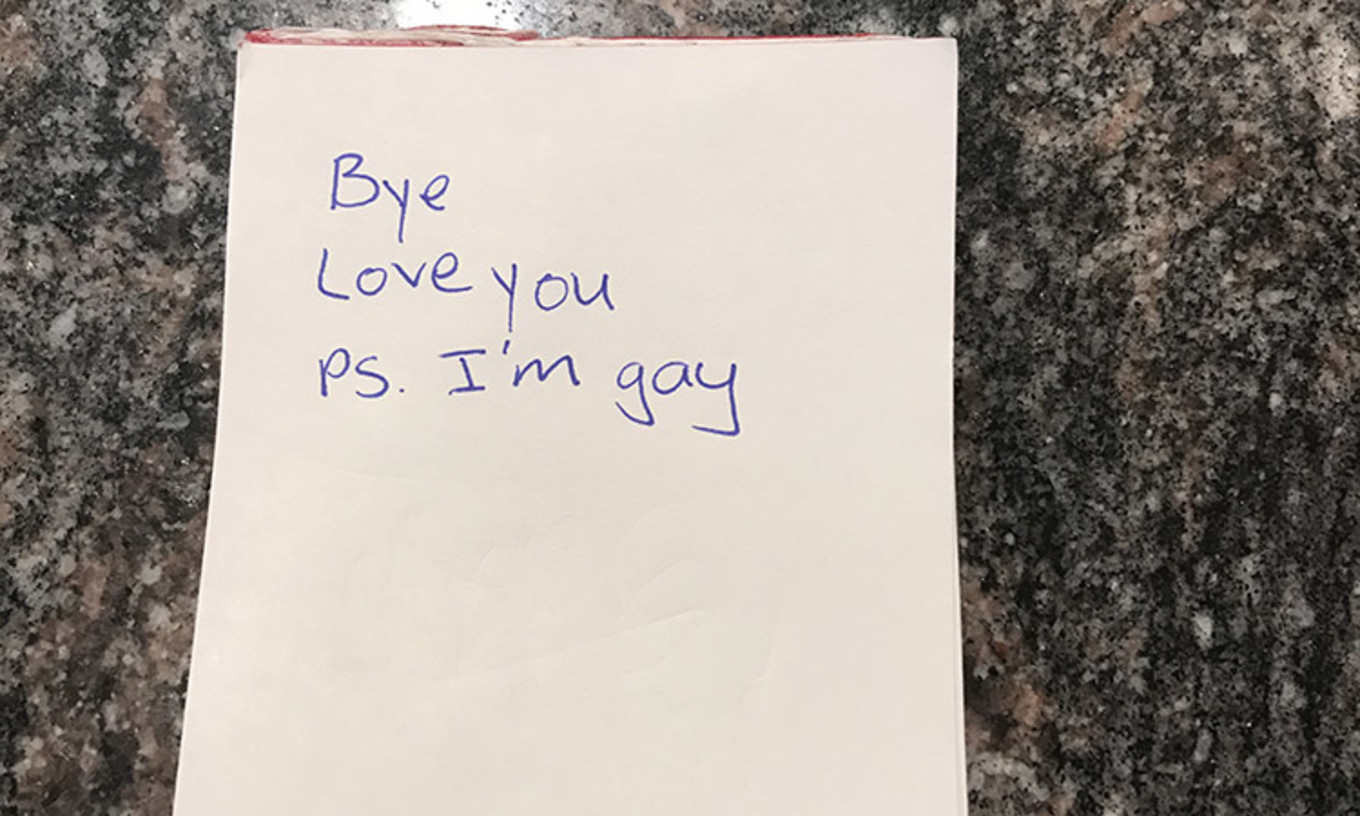

I had developed such contempt for the “coming out” process that, in a fight about absolutely nothing memorable at all, on my way back to New York City, I left a little, white sticky note on my mother’s door. It said, “Bye, love you, PS. I’m gay.”

It really is the most amazing way to win an emotional skirmish set in the war zone of a suburban household. “You have something to say about the way I do my laundry? WELL, TAKE THIS: I’M GAY!” There is no showstopper, no glorious rebelling of all the power dynamics between suburban parents and gay kids than weaponizing your authenticity. Nothing erodes the foundation of a McMansion than the personal earthquake your words can unleash within it. (By the way, the laundry thing was made up: I truly have no recollection over what the fight was about.) Eager to reclaim my own power, instead of asking my mother, “Do you love me for me?” I wrote a note that pretty much said “PS: I’m gay, and you will deal with it. BY YOURSELF.”

It really is the most amazing way to win an emotional skirmish set in the war zone of a suburban household. “You have something to say about the way I do my laundry? WELL, TAKE THIS: I’M GAY!”

Now, I just want to be clear: I am an experienced soldier in battles over setting the table and laundry duties, in car curfews and appropriate synagogue-wear. But I’m also a bit of a bee who has one poisonous sting in him before he plops to his death. And just like a bee, it seems I didn’t hit my target very efficiently. A full 24 hours after I left my note to total radio silence, my mother texted me: “I wish I had found your note before the cleaning lady did.” Oof.

My mother reveals her fighting skills: She knows that a cleaning lady discovering your dirty laundry is a tactical nuke of embarrassment. “Oh, you tried to cut me by unleashing a 'Dawson’s Creek'-level personal revelation?! Well, joke’s on you: Now our cleaning lady thinks you’re a psycho, and she doesn’t have to love you unconditionally.” It was the most Lucille Bluth moment she’s ever had. (She would not get the reference.)

“Are you protecting yourself against AIDS?” was the next question that came over text. I rolled my eyes. It was like doing battle with Soviet Russia: Didn’t we dismantle that whole "gays = AIDS" equation after Reagan? “Mom. I use protection,” I responded.

Photo courtesy of Ross Baron

Being "not a boy, not yet a grown man" means you become an expert at the condescending and stern tone a text message is perfect for. Finally, in the third sentiment, it came from her: “I love you.” Ironically, it mirrored how coming out was the third sentiment in my sticky note to her. And though she had finally said it, I remember feeling not one ounce of satisfaction. Was it even smart to use "coming out" in a fight at all?

For gay people, being themselves is a constant battle fought in tiny bits: what to wear, how to behave, who to be friends with, and most important, how much to even care. But fighting is expensive, and personal wars aren’t funded by money. They’re fueled by love. We only have the power to move forward and take on a world that is constantly fighting to marginalize us if our advancements are met with reinforcements. Yes, coming out is about power: a declaration about being strong within yourself. But a commander is only as strong as the army that surrounds him.

Perhaps my coming-out process would have been more emotionally fulfilling had I not acted as if my mother were an adversary or an ally, but just … my mother. She wasn’t concerned with the forces that treat my desire to be treated with dignity as an “agenda.” She wanted to know if I was safe, that I was loved.

For gay kids, areas that should be safe — like your home — can also be ground zero for trauma if your parents aren’t accepting. Had I come out by sitting my mother down, giving her the power to accept or reject, and been warmly received, some benefits would have included: a deeper connection with the woman who gave me life; a stronger foundation of love to face the world with; and a home environment where I was freer to be myself. But had she responded to my coming out with resistance, stereotypes, or rejection, it could have fundamentally damaged our relationship — and me — in ways that I wasn’t willing to risk.

So, I tried to avoid that power dynamic altogether. I was gay, and if she had a problem with it, she was going to have to deal with it herself. I sealed myself off from the benefits to minimize the risk. Who you give power to comes at a cost, but perhaps my mother was the one person I should’ve taken off the armor to face.

Few things speak to the chasm of what gay people experience versus what straight people think is important than the subject of coming out. Being queer is all about shattering norms. We think outside boxes and binaries. We learn that what is taught to be labeled and definitive is actually ever-changing and fluid. My coming-out story is constant — I told my first friend I was gay at 19, and last year, at 29, I told my grandfather.

I always get asked when I “knew” I was gay — as if it’s a moment with a beginning, middle, and end. But for gay people, there are two ways life progresses: one, the normal way, with aging; and two, where the arc of your universe bends toward authenticity.

Every day, you drift closer and closer to a more authentic version of you. There is no end. We are trees that have sprouted in very hostile terrain, and the longer we live, the bigger and more beautiful we grow, standing proudly and more defiant in a world that tries to cut us down. Aging just makes you realize that the difference between everyone being armed with chainsaws versus everyone being armed with plastic knives is the power you get from being strong within yourself. Openly.